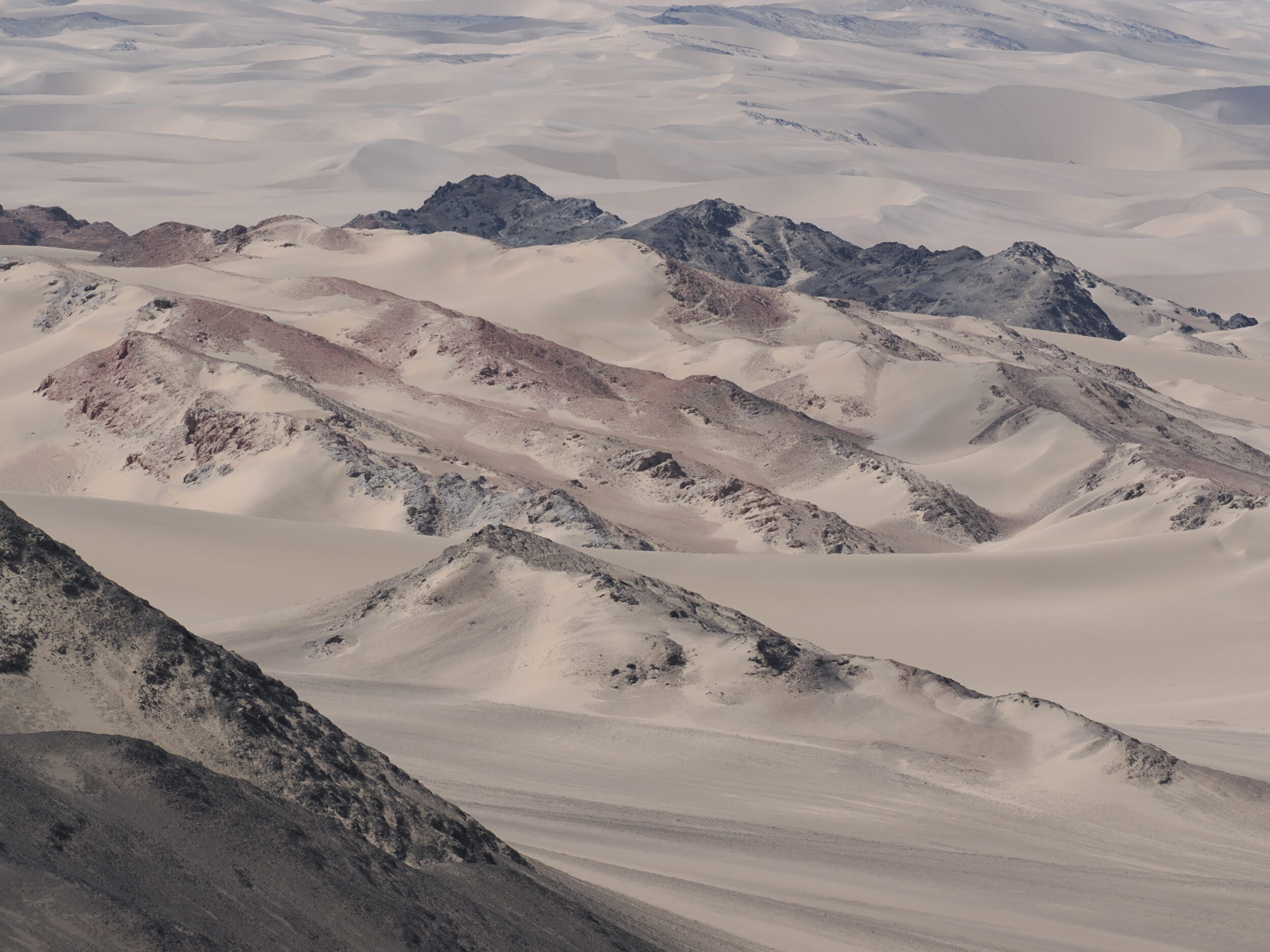

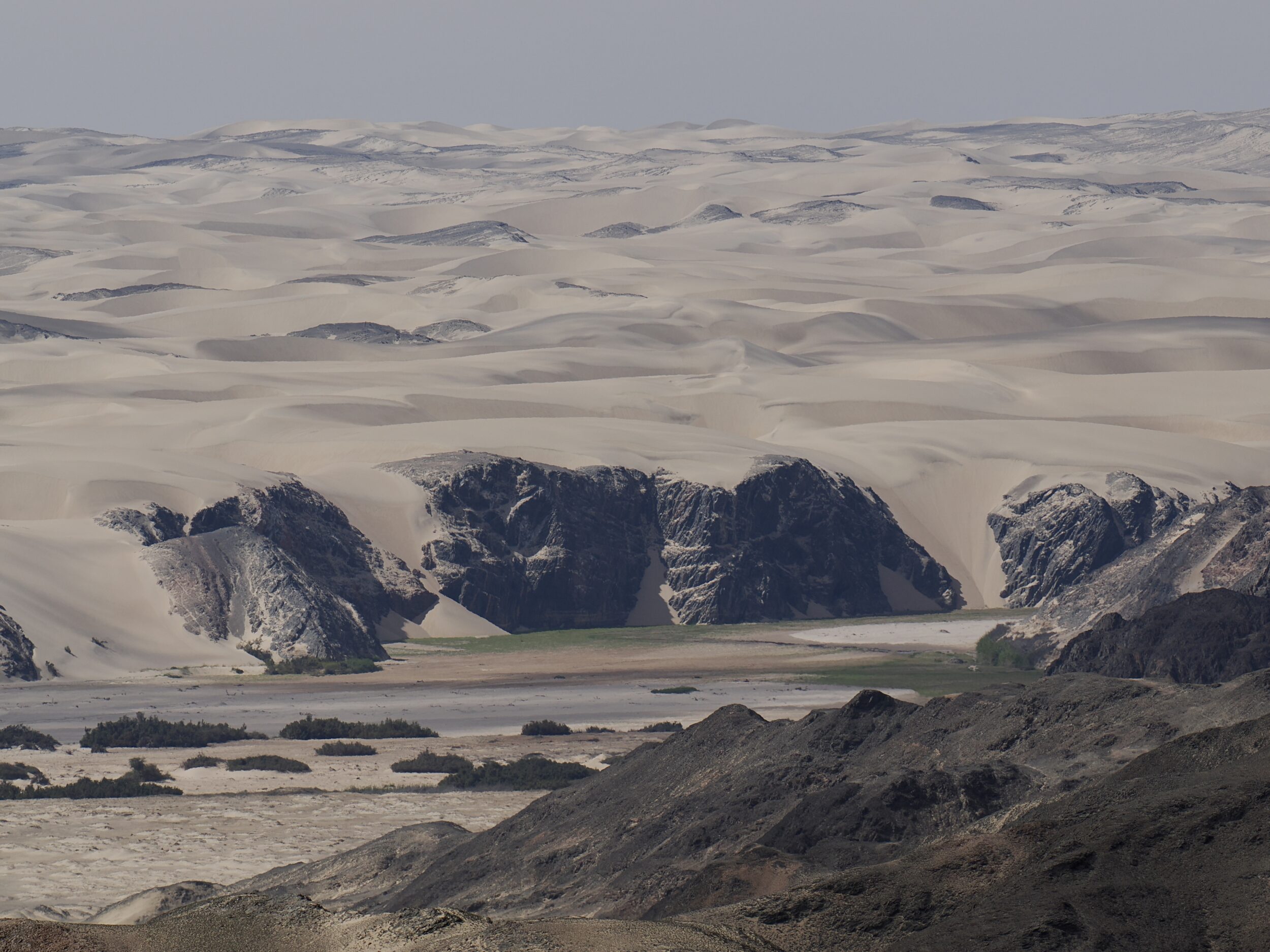

From 9.44 am through 10 am on 14 November 2022, the pictured rock and yours truly were sharing the very same hilltop.

Whilst the rock itself was an inanimate object, living beings very successfully occupied a deal of its exposed surfaces.

These beings are neither plants nor animals; as you can see, more than one species are obviously-present on this particular rock.

A lichen is a composite organism that emerges from algae or cyanobacteria living among the filaments (hyphae) of the fungi in a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship.

Comments closed