16 October 2022 was – even by Perth standards – a particularly benign Spring day.

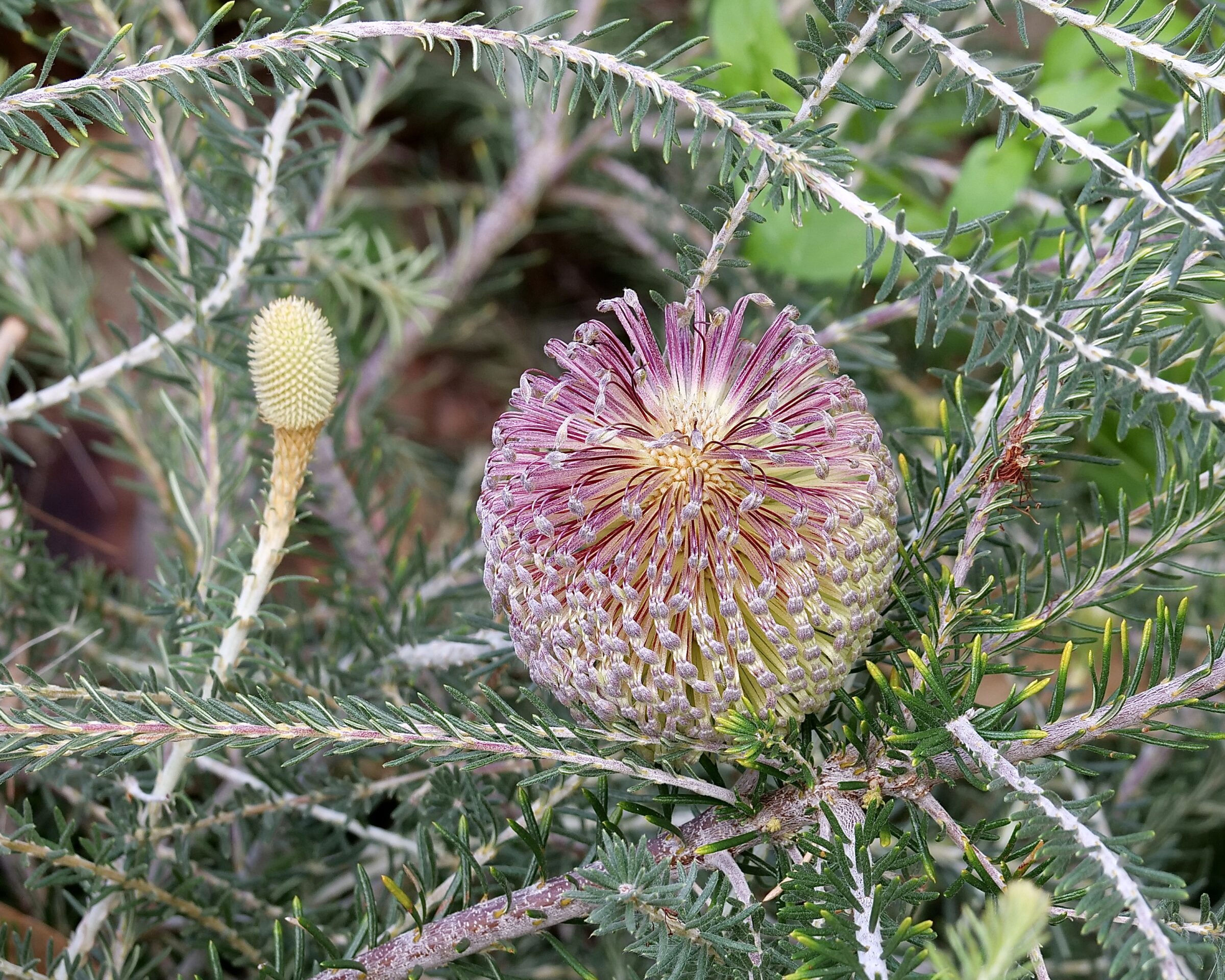

All photos in this post involved a long lens peeking over North Fremantle residents’ front fences, into gardens of highly diverse persuasions; the “unkempt” and the “manicured” proved equally alluring.

The two first images were taken from Stirling Highway’s western footpath; I suggest you zoom in/enlarge – the Hibiscus’s stamen is especially worth a closer view.

Comments closed