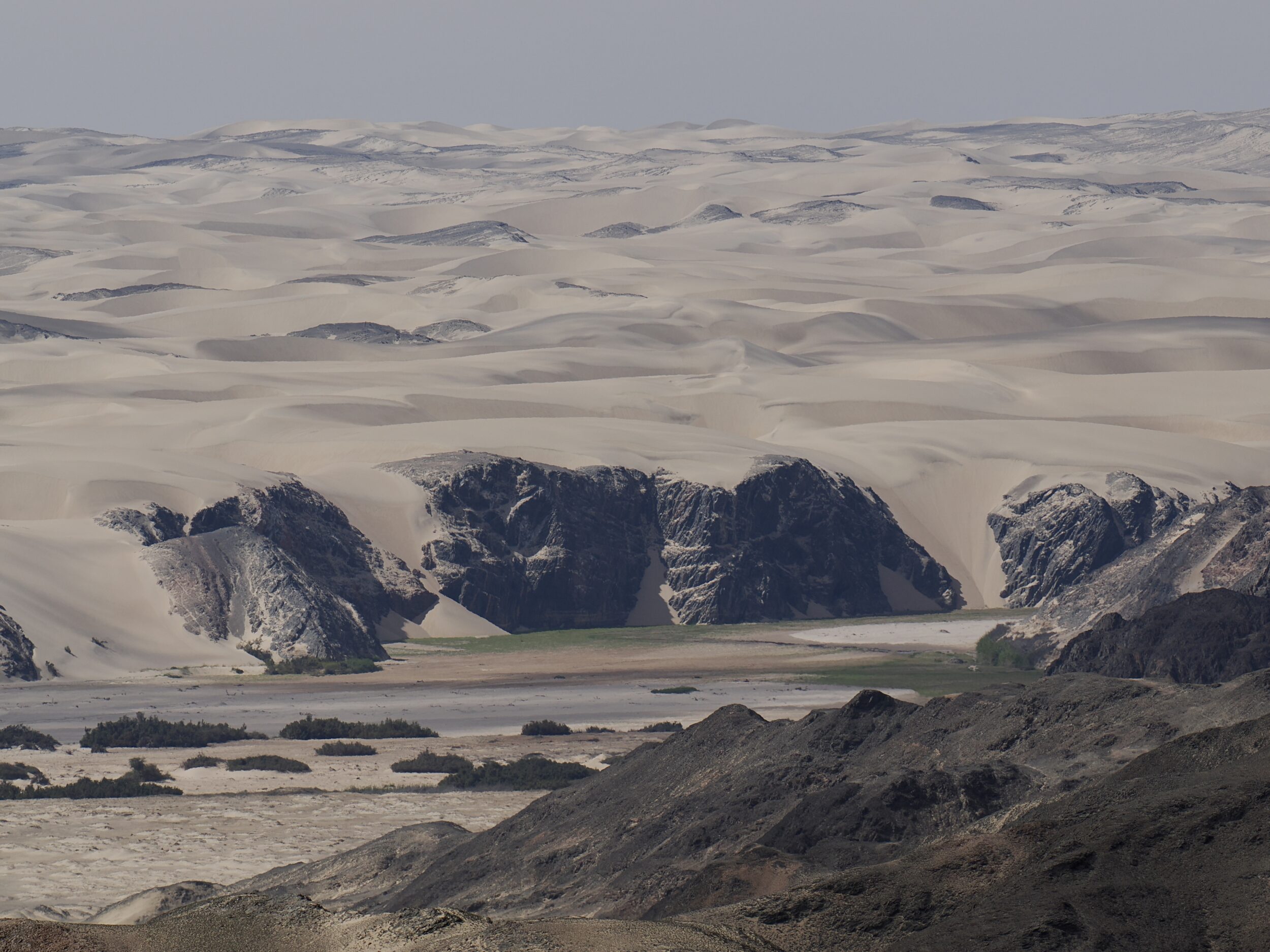

Although the vantage point remains the same, this post’s images were shot with a telephoto lens; effectively, their view of the Hoarusib River is nearly seven times “closer” than that offered by the image in this series’ previous post.

At this point, the river and its surrounding landscape are quite unlike where the Hoarusib – rarely, and briefly – delivers a readily-visible flow of fresh water to the “Skeleton Coast” edge of the Atlantic Ocean.

Yet, where I stood – and the stretch of the Hoarusib visible in these photos – are only circa 30 minutes’ drive from the river’s oft-dryish mouth.

In a straight line, the ocean is almost certainly rather less than 20 kilometres distant.

In some places – even where altitude change is slight – a very few kilometres can make a startlingly big difference.

We had a recent reminder of this.

On 19 February 2024, much of Western Australia was experiencing yet another day of a ferocious and prolonged heat wave.

When Perth reaches more than 40 degrees, it is not unusual for the very same day’s Albany maximum to be 25 degrees…or less.

Albany is 400 kilometres closer to Antarctica.

At lunchtime on 19 February it was 45 degrees in Perth’s Swan Valley.

My beloved and I were then 95 kilometres west of Albany, as we turned off the South Coast Highway, at Bow Bridge.

Even there, nearly 400 kilometres south of Perth, it was 36 degrees at 1.10 pm.

Less than ten minutes later, at essentially the same very low altitude, we had travelled just 9 kilometres further south, to reach Peaceful Bay…and its excellent fish & chips.

Those 9 ks delivered an 11 degree “discount”.

Circa 300 metres in from the Southern Ocean, the temperature was 25 degrees.

The near-Atlantic/“Skeleton Coast” edge of the Namib Desert is often pleasantly cool, and frequently shrouded in mist.

Venture just a few kilometres inland, however, and one is usually speedily reminded that Namibia is a land of generally high maximum temperatures, much sunlight, and very little rain.

Namibia has just five perennial rivers, which are all shared with neighbouring nations.

In the south, South Africa is on the other bank of the Orange River.

A significant portion of the Kunene/Cunene and the Kavango/Okavango divide northernmost Namibia and southernmost Angola.

Namibia shares smaller sections of the Chobe and Zambezi with Botswana and Zimbabwe, respectively.

The Hoarusib is one of Namibia’s twenty “well-defined” ephemeral rivers, all of which are Namibian on both banks.

The Fish River is the only one of those twenty which could be described, reasonably, as a “mighty” river.

(The Fish River Canyon is one of the world’s more spectacular canyons. It is often billed – falsely – as “the world’s second biggest canyon”. Also false: the claim that The Grand Canyon is the world’s biggest. Whatever the criteria – depth, width, length or volume – the USA is definitely not home to the world’s biggest canyon. Click here)

The Hoarusib Is circa 300 kilometres long.

Nearly all of its water comes from rains that fall on the hills and mountains near its source, where there is such a thing as a “rainy season”.

A few hundred kilometres in from the sea, northern Namibia is still relatively “dry”, but nonetheless enormously more “wet” than is its western/coastal/Namib Desert side.

In most years, for at least part of the year, one could reasonably expect to see water flowing in the Hoarusib’s upper reaches.

For most of the time, however, the visible flow will have petered out well before it gets anywhere near to the river’s mouth.